As accomplished strabismus surgeons, the physicians at Pediatric Ophthalmic Consultants are frequently asked to treat patients with unusual strabismus entities.

Although many of these patients can be categorized into well-defined categories, some patients exhibit complex combinations of vertical, horizontal and torsional strabismus. We treat patients with complex strabismus arising from thyroid related eye disease, stroke and brain tumors as well as strabismus disorders following severe orbital and head trauma. Nevertheless, what follows is a description of some of the common complex strabismus syndromes.

DUANE’S SYNDROME

Duane’s syndrome is a constellation of eye findings present at birth that results from abnormal connections among the nerves that supply the muscles of the eyes.

Duane’s syndrome occurs most commonly though not exclusively, in the left eye of females, who are typically otherwise healthy. Duane’s syndrome has several variants that present with various eye movement abnormalities. In the most common type, the eye is not able to move outwards from the normal straight ahead position. When the involved eye moves in the opposite direction towards the nose, the eye is pulled slightly back into the eye socket causing a narrowing of the opening of the eyelids. The eye may also drift up or down as it moves toward the nose. In addition, with the eyes looking straight ahead, they may be crossed in relation to each other. This may lead to a person with Duane’s syndrome to turn their head toward one side while viewing objects in front of them in order to better align their eyes.

Although restoration of full eye movements in patients with Duane’s syndrome may not be possible with eye muscle surgery, surgery can be beneficial for several indications. Surgical treatment can be effective for correcting any misalignment of the eyes which is present while looking in the straight ahead position, as well as eliminating any abnormal head positioning. If the abnormal up and down movements of the eye or the narrowness of the eyelid opening significantly affect the eye’s appearance, surgery may also be of benefit.

BROWN’S SYNDROME

Brown’s syndrome is a condition typically present from birth but at times acquired later in life in which the eye is unable to move up, especially when it is turned in toward the nose. This is caused by the inability of the superior oblique muscle, one of the eye muscles, to slide through its natural pulley system along the bony wall of the eye socket. This condition is often first noted in a child when the parent notes that the uninvolved eye is “floating” up when the child looks to the side, when actually it is the other eye which is not moving up normally.

Brown’s syndrome is often only an incidental finding on an eye exam in which case no treatment is needed. However, if the involved eye is lower than the other eye when the individual is looking straight ahead, or an abnormal head position is needed to keep the eyes aligned, eye muscle surgery can correct the problem.

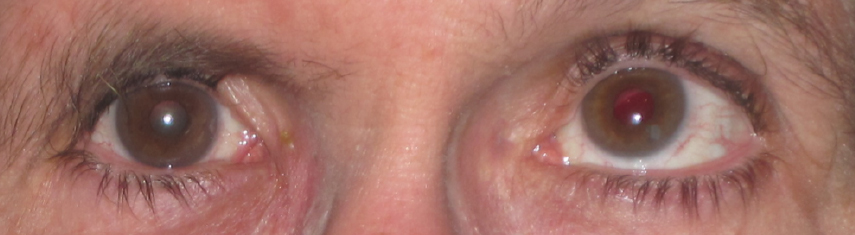

This child has a Brown’s syndrome of the right eye. The right eye is unable to elevate when turned towards the nose.

MOBIUS SYNDROME

Mobius syndrome is characterized by multiple disturbances of the cranial nerves supplying impulses to the muscles of the eyes and face. Most notable is the inability of one or both eyes to move outwards. This is often accompanied by eye crossing at birth which often needs to be corrected with eye muscle surgery. The involvement of the nerves that supply the muscles of the face is noted by early difficulty with sucking and feeding, as well as deficient closing of the eyes during sleep. The face can appear like a mask in that the ability to smile or wrinkle the forehead is absent.

Additional findings can be present as a result of problems with other muscle groups. There is often a partial paralysis of the tongue as well as the soft palate and the muscles of the mouth that control chewing. Muscles of the chest and bones of the hands and feet can also be abnormal.

THIRD NERVE PALSY

Third nerve palsy refers to a weakness of the nerve that supplies impulses to four of the six extraocular muscles and to the muscle that elevates the eyelids. This may be congenital or acquired following head trauma, brain tumor, stroke or cerebral aneurysm. The affected eye is generally misaligned outward (exotropia) and downward (hypertropia). At times there is an associated drooping eyelid (ptosis) or enlarged pupil.

Once we can document stability of the strabismus arising from a third nerve palsy (occasionally a congenital or acquired third nerve palsy can “regenerate” spontaneously over the course of 6-12 months), eye muscle surgery can then be performed to eliminate the ocular misalignment and restore single vision.

FOURTH NERVE PALSY

Fourth nerve palsy refers to a weakness of the nerve that supplies impulses to the superior oblique muscle, a muscle of the eye which has the main function of moving the eye downwards.

If this muscle is weak, the eye tends to drift upwards. (see the Hypertropia section for more information)

SIXTH NERVE PALSY

Sixth nerve palsy refers to a weakness of the nerve that supplies impulses to the lateral rectus muscle, the muscle of the eye which is responsible for moving the eye outward. This is usually an acquired condition which can present with the gradual or sudden onset of eye crossing often accompanied by double vision along with an inability of the eye to move outward. An abnormal face turn may occur in order to relieve the double vision. In children, the most common type of sixth nerve palsy is one which can be recurrent and is thought to be related to a viral illness. Other causes in the young age group include head trauma and other brain disorders. “Small blood vessel disease” resulting from diabetes or high blood pressure are common causes of sixth nerve palsies in adults.

Sixth nerve palsies generally improve over the course of several months. After a period of observation, if the recovery is incomplete and a residual eye crossing remains, eye muscle surgery can eliminate the eye crossing and relieve symptoms of double vision.

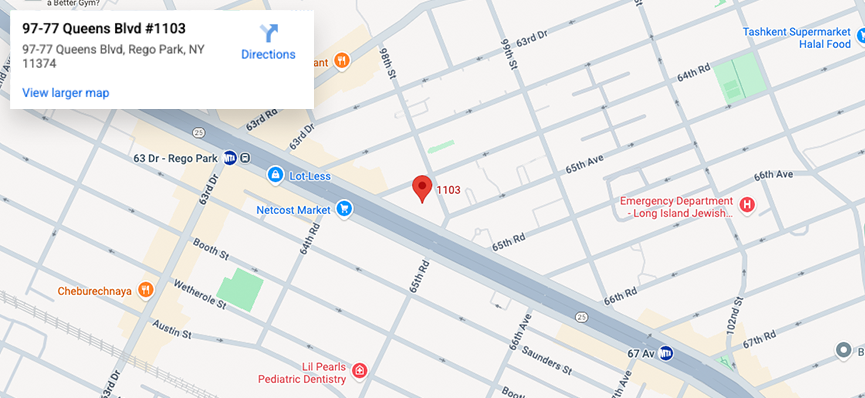

Pediatric Ophthalmic Consultants

40 West 72nd Street, New York, NY 10023 | 212-981-9800

The content of this Web site is for informational purposes only. If you suspect that you or your child has any ocular problem,

please consult your pediatrician, family practitioner, or ophthalmologist to decide if a referral to a pediatric ophthalmologist is required.